Paul Roos is an AFL legend. After a hugely successful playing career, he became a coach and guided the Sydney Swans to the 2005 Premiership, their first title in 72 seasons. Dylan (24) is one of Paul’s two sons. But what’s it like being brought up by the 2008 Australian Father of the Year?

Dylan: Your number one value? Everything you do is for family. You don’t really do anything else. You have no other driving force.

Paul: I have you and Tyler (his other son) I have Tami (his wife), yes, but I have some friends.

Dylan: He has no friends. He has three friends. He has John. Rossy. One more…

Paul: Steveo.

Dylan: Steveo. There’s your friends.

Paul: There’s also Lynchy and all my old footy buddies. But I think what Dylan’s saying is right. I would probably generally prefer to spend time with my family than anyone else. That was 100 per cent, I could say that without any fear of contradiction. If someone said, “Roosy, do you want to come to the pub, or play golf or whatever,” … Not that I didn’t like doing other stuff, but I’d always say, “Dylan, what are you doing today?” If the kids are busy, then I’ll go and play golf.

Dylan: It’s always been like that. When I was growing up, dad was always there. He was never not there. He’d be playing in Perth on a Saturday, catch the red-eye flight 12 o’clock, and be there at my game, 8am Sunday morning. That was huge. That’s something that you probably don’t notice as much at the time as you do looking back.

I expected him to be there. I didn’t know any different. I didn’t realize that was something that most dads probably wouldn’t have done. We had weekly breakfasts at a café during Primary School that were never cancelled. Thursday morning at 8am before school, every week with my mum and my brother. There are sensory memories. The smell of coffee and the noises of a café. I remember we used to do math games, and we used to see how far we could double the numbers. I’d start at two, and go, “Two, four, eight, 16, 32, 64, 128,” and I’d see how far I could go each time.

I think you have to get some of the dad things right from the get-go, because you don’t get the time back. But also because that’s the time that you’re most malleable as a kid, is when you’re younger. Zero to seven are the formative years, when you’re pretty much going to learn everything you are about your parents, and after that, good luck.

Paul: My dad was different with us. It was just a different time. We would do things together, but separately, if you know what I mean. We would play at the same tennis club, but I was in a different tennis team. Dad was president of the club, and on the board of the Primary School and Beverly Hills footy club. Whereas I was probably more hands-on. I would coach them, or I would play tennis with them. My dad was around us kids. I was with mine. I was just more inside the family rather than part of the family, if that makes sense.

My biggest challenge as a dad has been words, rather than actions. I think my actions with Dylan are really good, but I’m not always good with words. My mum and dad split up when I was nine, and at 20 I was out of the house. Dad got remarried, had this sort of different life after us. It wasn’t like we didn’t get on; we always got on really well. We just didn’t have conversations.

I think Dylan will be a more engaging father, in terms of vulnerability and definitely in terms of communication, which I think is what we need. That conversation around males is changing, but it also makes it harder in a way, because when I was his age I thought I knew what my role was. You go to work, be tough, play sport. It was pretty defined.

Dylan: The other day I was just sitting at a café with one of my mates, and we were talking about how we were soulmates, and our thoughts around that. Correct me if I’m wrong, but you and your mates would never sit post-game of footie, talking about soulmates. So, I think we’re levelling up in terms of our emotional intelligence.

Paul: I think that’s the level of conversation that you’d love this next generation to have. The pub talk is not about sport. Sport’s part of it, but the pub talk, the coffee talk is more around, “How are you going as a dad? How are you going as a bloke? How are you going as a mate?” Getting underneath those conversations.

Dylan: Dad has said a couple of times that he hopes he raises two men, me and Tyler, to be better than what he was. I hope that as well. As much as I love and respect my dad, I hope I’m a better father than him; not because he was a bad father, but because you want to learn from your own experiences as a kid and then improve upon it.

Paul: I hope he’s equally as family-oriented, equally as honest. I think some of the things he’s talking about today are great.

Dylan: What you realise as you get older is that your parents are people, too. They make mistakes and you have to forgive them for the mistakes they’ve made, because there’s no blueprint for being a parent. When I have kids one day, I’ll probably realize that a lot clearer. if you can admit your mistakes to your kids, they’re probably going to forgive you.

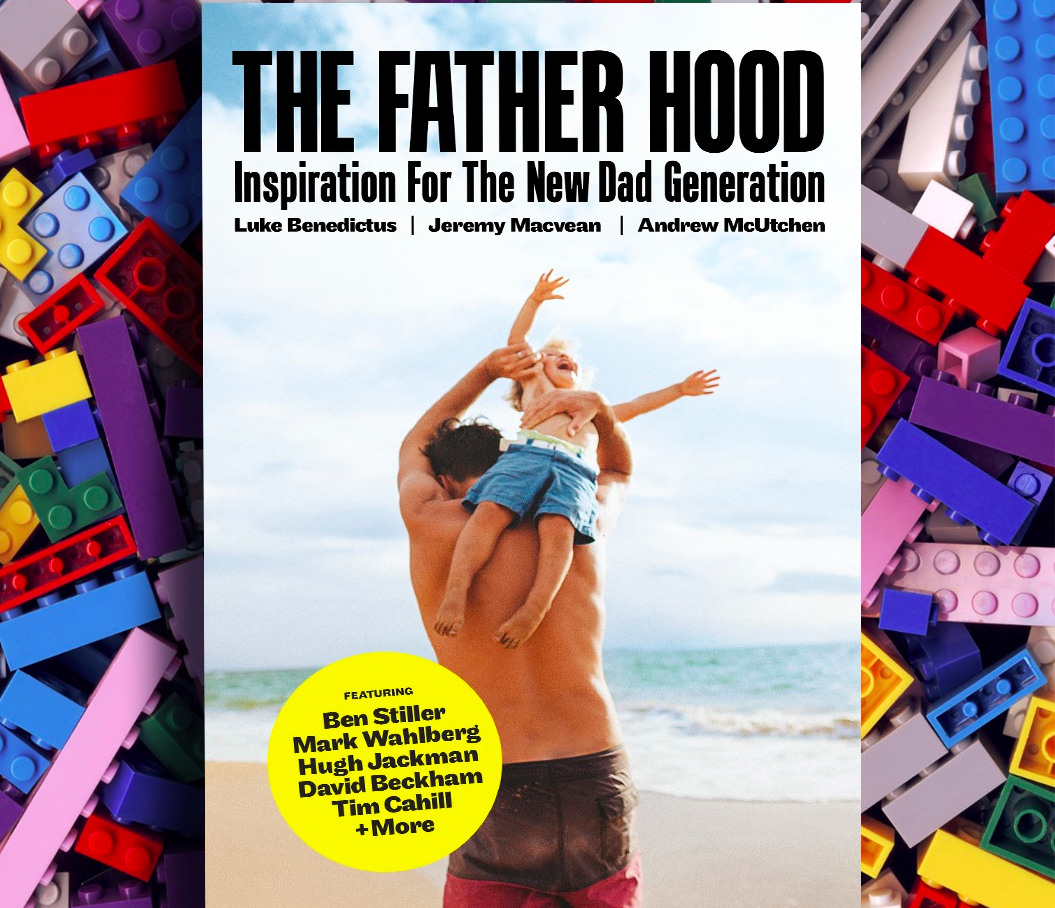

This is an extract from The Father Hood: Inspiration For The New Dad Generation. Buy it here