Modern fatherhood has a new leading man. Forget George Clooney (too slick), Jamie Oliver (too busy) or The Rock (looks too much like a thumb). No, the father figure any man should now model their dad-game on is, in fact, a cartoon dog from the Brisbane suburbs.

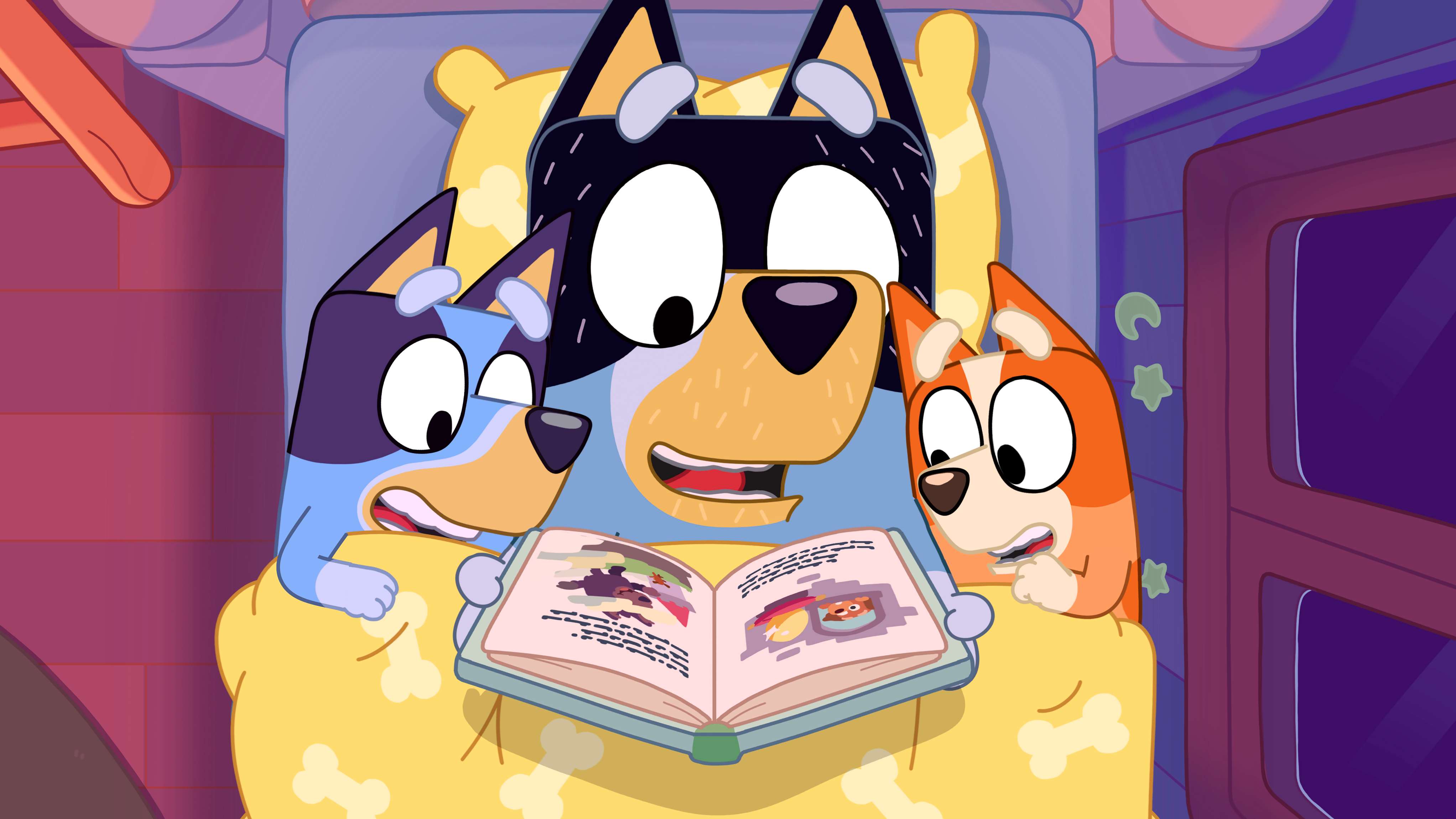

Bandit is the dad in Bluey, the hugely successful animation series that’s leapfrogged PlaySchool and The Wiggles to become the No.1 show in ABC iView history. It charts the domestic life of the titular blue-heeler pup who lives with her parents and four-year-old sister, Bingo, in Brisbane.

For a kids’ TV show that setting is significant. Bluey unfolds in a world of lorikeets, backyard barbies and jacaranda trees. In short, it’s a home-grown series that’s as fair-dinkum as Bob Hawke skulling a beer at the Boxing Day Test.

“I wanted to get an Australian feel that wasn’t the outback and kangaroos and koalas,” explains Joe Brumm, the series creator. “I just thought that’s pretty well-worn. What I wanted was suburban Australia.”

Equally refreshing is Bluey’s take on fatherhood. Bandit is a laid-back but resourceful dad who’s heavily involved in the day-to-day childcare. In his home office, he sits on a yoga ball at his desk because, as he explains to Bluey, “I wrecked my back changing your nappies”. From cleaning to washing to school runs, Bandit navigates the drudgery of household life with calm assurance. “He’s actually really competent,” Brumm says. “He’s a good dad.”

In the animated universe, this makes him something of a rarity. After all, from King Thistle to Homer Simpson, cartoon dads tend to be half-wits or buffoons. The father in Peppa Pig is a text-book example. Daddy Pig is a good-natured glutton with a “big tummy” whose efforts at map-reading, barbecuing or DIY – the stereotypical mainstays of paternal expertise – always end in disaster. Asked to draw a picture of a vegetable to take in to school, Peppa sketches her dad slumped in front of the TV.

Not everyone laughs off all this “silly daddy” stuff either. In a survey by mothering website Netmums, 93 per cent of parents agreed that the media depiction of dads failed to reflect what they contribute to real family life. Almost half said that such portrayals could make kids think that dads are “useless” while 28 per cent claimed the shows were a “very subtle form of discrimination” and there’d be uproar if the same jokes levelled at dads were fired at women, ethnic minorities or religious groups.

Eyed from this context, Bandit’s character seems loaded with extra significance. Is he a four-legged counter-attack for gender equality? The truth is actually far more heartening: Bandit, it turns out, isn’t some figure of political allegory, but a straight-up depiction of the here and now.

The inspiration for Bluey is primarily observational, Brumm explains. In that respect, Bandit’s approach to parenting simply reflects the animator’s own experience and that of his circle of brothers and mates.

“He’s like every sort of caring dad these days,” Brumm says. “They’re across everything – the housework, kids, work, the lot. Compared to my dad’s day, we’ve just had a slow, generation-by-generation change to the point we’re at now, where being a dad just seems like an all-in.”

The “majority” of Bluey is biographical with Brumm sharing many characteristics with Bandit. He’s the father of two small girls too and, running his own animation company, he largely worked from home in their early years to become an active figure in their daily lives. “I mean Bandit is a much better dad than me,” he says. “But when you write a cartoon, you can obviously cut out the shortcomings that I have as a dad. Which are definitely numerous…”

Yet there’s one area, Brumm concedes, where Bluey does get “vaguely political”. The cartoon resolutely champions the importance of play.

Bluey was still in embryonic form when Brumm’s eldest daughter started school. Her experience changed the course of the show.

“Play time was suddenly taken away from her, it was just yanked and seeing the difference in her was horrendous,” he says. “There was no playing, there was no drawing, it was just straight into all this academic stuff. And the light in her eyes just died.”

The family subsequently changed their daughter’s schooling after Brumm began to research the value of play for child development. Mastering these soft kindergarten skills, he found, is a vital stage in kids’ evolution into socially aware creatures. Their make-believe games can deliver self-taught but powerful lessons about how to co-operate, share and interact.

“Bluey is just one long extrapolation of that,” Brumm says. “It’s to encourage people to look at play not just as kids mucking around, but as a really critical stage in their development that, I think, we overlook at their peril.”

This shift in focus had a massive impact on the show. Zeroing in on imaginative play and the wacky scenarios this threw up, helped to unlock Bluey’s creative potential while maintaining its observational stance. Crucially, it also allowed Bandit to maintain a degree of dignity while still being a comical character.

The father plays a central role in these madcap games with his kids. One minute he’s pretending to be a “magic claw” vending machine; the next he’s immersed in an Indiana Jones-style adventure dodging a giant yoga ball.

“But because the show is so focused on play, it’s perfectly fine that someone who is a confident and caring dad could just switch into these Monty Python scenarios and not be a complete fall-guy and moron,” Brumm explains. “You believe it and the kids still laugh at it. But you’re left with a more nuanced character, one who you can respect for his dedication and who you can also laugh at”.

Yet while Bluey is a show about play, that doesn’t mean it’s all fun and games for the adults. This isn’t a saccharine portrayal of fatherhood – Bandit’s coat is flecked with grey hairs for a reason. The show refuses to flinch from the fact that parenting is bloody hard work.

Bandit never gets to do anything he wants to as his desires are constantly subjugated to the whims of family life. Attempts to read the newspaper or work from home are invariably sabotaged by the kids. When Bandit and his brother try to watch the cricket, they’re forced to play “horsey weddings” instead.

The selflessness that fatherhood demands is made explicit in the episode, Fruitbat. Bluey creeps downstairs one-night to see her dad fast-asleep with a rugby ball tucked under his arm. Bandit, we see, is literally dreaming of playing sport and hanging out with his mates. “He doesn’t get to play touch-football any more because he’s busy working and looking after you,” his wife explains.

“When you become a dad you are propelled into one of the biggest learning and sacrifice periods, you’ve got in your life,” says Brumm. “Suddenly, the last vestiges of your selfishness are just thrown to the wind. When the kids come along it’s like: ‘Well, your wants and needs are now completely irrelevant. You’re here to provide’.”

“For me as a dad, that was quite difficult. And we try and show that with Bandit. In an episode like Fruitbat, the point was to show all the things he really wants to do, he doesn’t get to do. There’s a few echoes of longing from him, but there’s not a trace of regret. Bandit is happy with the trade he’s made. He’s accepted it. And it’s such a beautiful trade…”

Brumm knows what he’s talking about from his own experience of fatherhood. Between mastitis, asthma attacks, emergency trips to intensive care and “real bad sleep”, family life has often provided a bumpy ride.

“Since becoming a dad, it seems like I’ve had more major problems in the last eight years than I had in the previous 32,” he laughs. “Sometimes I just think, ‘My God, it’s like I’ve started some post-graduate degree in pain’.”

“But I love who I’ve become because of it. I mean, obviously, you’ve got these kids, which is great. But you also become so much tougher. I could never have done something of the scale of Bluey without being through those experiences and that process of hardening up.”

Such reflections on parenthood quietly inform the show. Scattered through the episodes gleam bright moments of paternal inspiration.

They’re apparent in an episode like Takeaway, when a straight-forward trip to the local Chinese turns into a slapstick disaster. Kids need the toilet at tricky moments; a tap faucet gets stuck, the long-awaited food ends up scattered in the gutter. But just as Bandit begins to despair, a fortune cookie delivers some timely perspective on the fleeting nature of childhood. “Sometimes you need those reminders,” says Brumm.

He mentions the episode Bike in which Bluey is struggling to learn how to ride her bike while her friends encounter their own playground complications. Spoiler alert: perseverance ultimately pays off. Yet Brumm says of that episode, “if there is any type of message, it’s aimed at the adults rather than the kids.”

“Bike, really, was just about my experience of parenting,” he says. “It’s really hard, it’s quite brutal, but you just keep turning up. You just keep trying, and hopefully, it all works out. Don’t give up.”

It’s a message that delivers more reassurance than any childcare manual. When you’re waist-deep in the swirling chaos, fatherhood can feel like a battle to keep your head above water. But as Bandit – the spirit animal of the modern dad shows – you can always resort to doggy-paddle.